Analysis of Vogue’s “Fashion: The Straight and Narrow Way”

- Apr 2, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 22, 2025

“Fashion: The Straight and Narrow Way” (pp. 84, 85, 100, 108) from Vogue’s February issue in 1925 (Vol. 65, Iss. 4, Feb. 15, 1925) reflects the transformative 1920s, a decade of change for women. After entering the workforce during the war, women embraced new social roles and gained the right to vote, further empowering them. This shift gave rise to the flapper — young, fashionable, and liberated women who rejected traditional gender roles. With the euphoria of the war’s end, women flocked to dance halls, jazz clubs, and speakeasies, joining in activities once reserved for men, like smoking and drinking. This cultural shift influenced fashion, as women moved away from Victorian-era restrictions. The era’s androgynous trends — shorter hemlines, looser fits, and dropped waistlines — reflected their growing autonomy. In this article, targeting affluent, fashion-conscious women, Vogue recommends corsets, brassières, and lingerie designed for various body types to help women achieve the ideal shape of the era.

The article opens with a satirical comparison of shifting beauty ideals, imagining a contest between three archetypal female figures: the Venus de Milo, the 19th-century “hourglass lady,” and the modern “flapper,” judged by Father Time. While Venus may favor the flapper over the hourglass lady due to similar body proportions, the flapper is depicted as fragile and unsuitable for domestic duties. This satire reflects 1920s concerns about women’s independence and whether they could balance traditional roles with newfound freedom. The article highlights how beauty standards evolve, noting that the once-coveted hourglass figure is now seen as needing a hip reduction, while even Venus would require a corset to meet modern expectations. Vogue identifies slenderness, with a flat back and relaxed appearance, as the era’s beauty ideal.

Vogue discusses the return of the once-“hated stays.” This garment was rejected during the war era when women entered the workforce in place of men, prioritizing movement and comfort. However, Vogue now celebrates modern corsets, offering a variety of styles and adaptability to suit different body types and occasions. The garment’s resurgence comes as women, upon seeing unflattering reflections in mirrors, realized that their more sedentary lifestyles had led to wider hips and a less “boyish” silhouette. This revival demonstrates how fashion trends often cycle back and evolve, as seen with “stays” now being updated as corsets.

While corsets were not new, advancements in materials and design, such as elastic fabrics and satin brocade, replaced the rigid whalebone versions of the past. The article highlights these innovations, noting that for women with wider hips or figures lacking the desired straight lines, a longer, well-constructed corset made from firm boning and durable fabrics like pink brocade is essential to achieve the “straight and narrow” silhouette. One particularly effective model, “number III,” is advertised as capable of reducing a woman’s hip measurement by five to eight inches in a short period. Throughout the article, Vogue references and commodifies specific models, reflecting the magazine’s shift toward a more commercial role and its growing focus on product promotion.

The article highlights the variety of corsets designed for specific types of women. It advises against elastic back sections for those with an unflattering backline, as they lack structure. For “eternal Peter Pans” — women who stay slim effortlessly — a small girdle with buttoned elastic straps is ideal. These women are considered “lucky creatures,” reinforcing the notion of thinness as desirable. Older women may prefer firmer girdles for daytime, pink brocade for evening, or combined girdles and brassières with decorative straps for evening and linen versions for sports. This distinction in corsetry reflects how fashion imposes expectations on women to conform their figure to the idealized standard. The emphasis on proper corset wear — including daily lace adjustments — reinforces how fashion remained a form of discipline.

The brassière became just as crucial as the corset in defining the female silhouette. While corsets shaped the waist, brassières contoured the bust. For petite women with some fullness, the article recommends a simple silk batiste brassière which offers support while preserving the desirable “boyish line” that minimizes curves. Women with a larger abdomen benefit from a side-tricot, batiste, and elastic brassière designed to smooth and support the lower torso. Those with fewer shaping concerns could wear wide satin ribbon brassières with underarm darts. The preference for natural slenderness is clear, as fuller figures require more corrective garments to achieve the ideal shape.

For ultimate figure enhancement, Vogue advises custom-made corsetry, encouraging women to visit top corset makers annually and order multiple corsets for different occasions. While Vogue says pink remains the most popular choice, some women prefer black corsets for travel due to their practicality and ease of maintenance. This focus on made-to-order corsets reinforces that achieving the ideal silhouette requires both customization and investment. The preference for black corsets highlights how even practical wardrobe choices were influenced by social expectations, showing that women’s fashion remained carefully curated despite the flapper era’s carefree spirit.

The focus of the article then shifts to lingerie, which has become simpler and less adorned than in previous years. Gone are the billowy ruffles and excessive embellishments of earlier styles; instead, it now follows the simple, straight lines of contemporary fashion. The combinaison pantalon and combinaison jupon reflect this shift toward functional undergarments, crafted from soft, luxurious fabrics like crêpe de Chine. These garments offer shape without bulk and allow for movement, aligning with the flapper’s active social life, where freedom of movement and a sleek appearance were key for nights out.

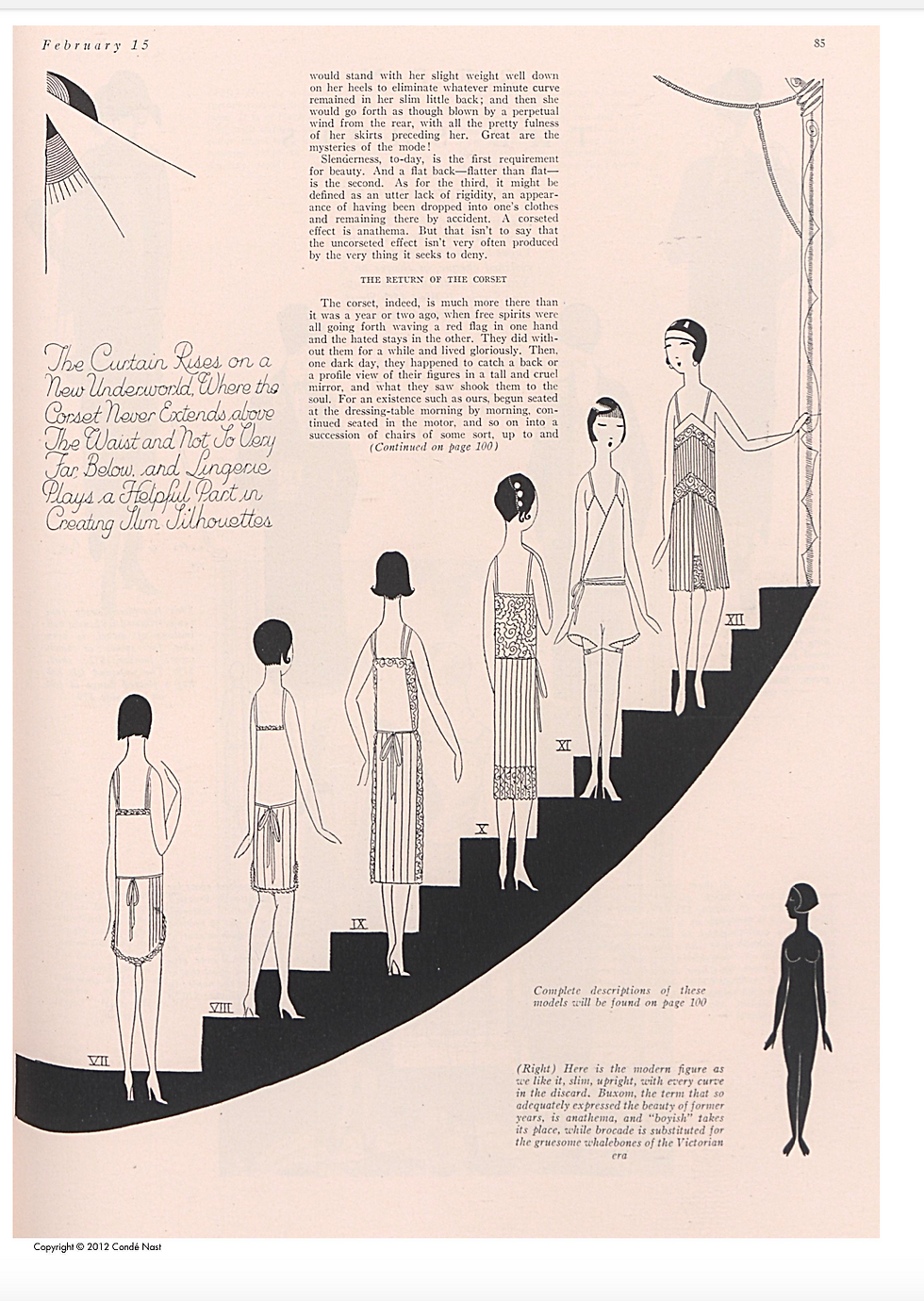

The illustrations in the article exemplify the content. They are drawn and presented in black and white, reflecting the early 20th-century style of fashion magazines when black-and-white print was standard. Choosing illustrations over photographs allows for a more stylized, idealized depiction of the female form, emphasizing the desired silhouette rather than realistic bodies. These illustrations not only set the mood but also visually support the text’s claims. The first image presents a staircase-like progression of women in various stages of dress, demonstrating how undergarments shape the figure. The second image, an advertisement, combines text and visuals to promote a specific corsetry brand, Redfern.

On the spread on pages 84 and 85, aside from the slim, boyish figure favored during the era, it’s notable how corsets and girdles are marketed to shape the body into a fashionable form. The bob haircut represents a controlled, styled look for the head, known as a garçonne — a nod to the French word “garçon,” meaning “boy” — as flappers rejected traditional femininity for a more androgynous style. Additionally, the figures are depicted with a “flapper slouch,” reflecting the carefree, rebellious spirit of the time. The V-shaped staircase layout creates a balanced composition, highlighting both order and modernity, evoking the dramatic entrances of Art Deco architecture. The linear arrangement of figures with streamlined poses reflects the movement’s emphasis on symmetry and sleek lines. Their minimalistic faces prioritize uniformity over individuality, and the title, “The Straight and Narrow Way,” contrasts with the geometric design.

At the bottom left of the spread, on page 84, is a silhouette of a woman in the Victorian hourglass figure, created by rigid, uncomfortable corsets with whalebones. The term “shudder” conveys revulsion towards this extreme, unnatural shape. In contrast, the bottom right image on page 85 shows a modern, slender, straight figure, rejecting past curves. The term “buxom” is deemed outdated, while “boyish” is preferred, reflecting a shift towards comfort with softer fabrics like brocade replacing the restrictive whalebones. Together, these images illustrate the cultural shift from corseted curves to slim, straight lines as the new beauty ideal.

On page 100, the magazine advertises the new approach to corsetry that aligns with contemporary fashion trends by shifting the focus from the waistline to the hips and back. Traditionally centered on the waist, the corset is now designed to slim the hips and create a flat back. The ad highlights Redfern’s latest innovations, such as the Redfern Wrap-Around, Redfern Corselette, and Redfern Rubber Reducing Garments, all of which feature this updated technique. Captions accompany these images, explaining the corsets’ functions. The section concludes with a reminder to choose original Redfern designs, cautioning that cheaper imitations may not deliver the same results. This shows how the article is specifically aimed at women who can afford high-end corsets and lingerie from prestigious fashion houses.

Vogue encourages readers to embrace the updated version of the corset as a crucial tool for achieving the slim ideal. Through illustrations, the magazine recommends a variety of corsets, brassières, and lingerie tailored to different body types, with Redfern’s designs highlighted as the ideal choice. Despite being written at a time when flappers were challenging traditional gender roles and rejecting restrictive garments in favor of looser, more carefree styles symbolizing their growing independence, Vogue continues to reinforce beauty standards for women, even though the article initially acknowledges the challenge of shifting beauty ideals. This shows that while the movement towards liberation marked progress, it was simultaneously shaped by mass media. Even as women sought greater independence, they remained influenced by fashion trends, demonstrating that their autonomy was still intertwined with the pressures of conforming to ever-evolving beauty standards.

Cole, Derek, and Nancy Deihl. “Chapter 5: The 1920s: Les Années Folles.” The History of Modern Fashion, 2nd ed., Laurence King, 2015, pp. 129-160. Ebook Central, ProQuest, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com

"Fashion: The Straight and Narrow Way." Vogue, vol. 65, no. 4, 15 Feb., 1925, pp. 84-84, 85, 100, 108. ProQuest, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fmagazines%2Ffashion-straight-narrow-way%2Fdocview%2F879165070%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.